I recently indulged in the BBC film Life Story. I am a sucker for biographies (and sometimes autobiographies) of the ‘Great and Good’ of science and the many accounts of the discoveries surrounding deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA) are some of the best reads and watches.

While Jim Watson’s account doesn’t always tally with those of Crick or Perutz or Bragg or Franklin for that matter, it is an exciting watch, at least for me. It reminds me of my own joy of doing science, of being in the laboratory and of the anticipation of discovery.

I have been lucky (like Lucky Jim as they called Watson) having experienced the excitement of ‘discovery’ on more than one occasion. I have written about some of these moments in previous substack posts.

The unravelling of the structure of DNA as depicted in Life Story reminded me in particular of our research on hydroxyaluminosilicates (HAS). We didn’t have X-ray crystallography to help us to understand the structure of HAS as they are amorphous, semi-crystalline structures at best. However, we learned how to precipitate HAS from pure solutions and analyse their structure using a battery of analytical techniques including most critically nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). The first NMR data on HAS isolated in my laboratory were obtained by my Belgian PhD student Fred Doucet. I remember clearly the moment when he rushed into my office and excitedly announced that there wasn’t just one structure, one HAS, but two distinct forms. No, I said, bringing him back down to Earth with a bump, that cannot be true, you must have made a mistake, go back and repeat the measurements (no trivial task as those who have worked with Si and Al NMR will know). I knew then that there had not been any mistake, it was simply good practice to make him repeat his experiments.

This ‘discovery’ was published in Geochim Cosmochim Acta (the leading geochemistry journal at that time) in 2001 and we spent the next dozen years or so adding grist to the mill without being able to provide unequivocal proof of our two different forms of HAS. Our Watson and Crick moment (when they saw the crystallography data for the B form of DNA) came through the unlikely route of another of my PhD students, James Beardmore. Well, unlikely because James was a computational physicist and my grasp of computers was basic at best. However, we formed an ‘odd couple’ and James excelled and completed a first class PhD (see my substack post on The Blood Aluminium Problem). Replete with new skills in computational chemistry we teamed up with my great friend and colleague Xabi Lopez (San Sebastian, Spain) and turned our attention back to HAS.

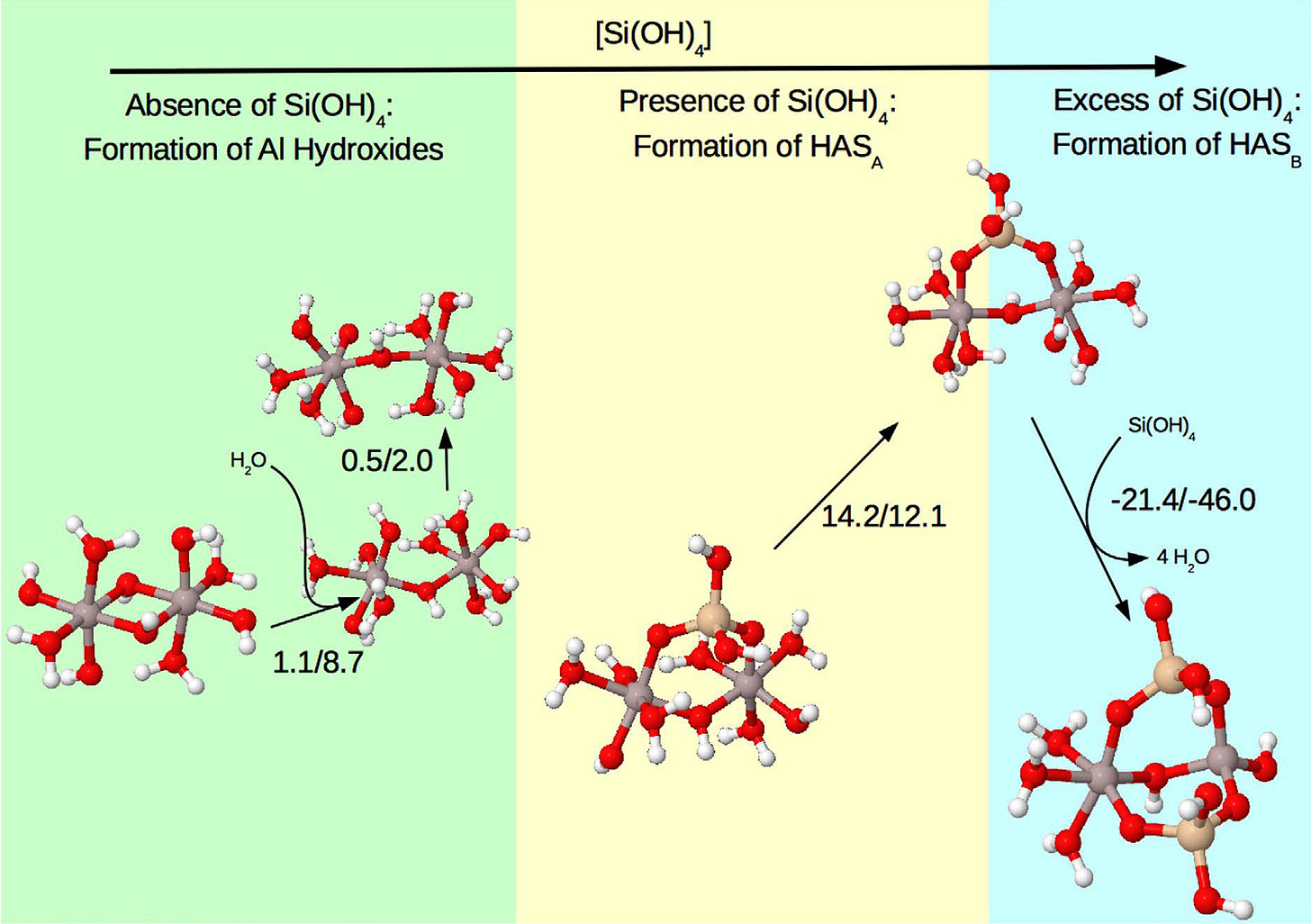

The task was to use a computational chemistry approach to confirm unequivocally the formation and hence structure of the two primary forms of HAS, HASA and HASB. Something perhaps akin to the model building used by Watson and Crick. If computation would confirm the structure and stability of the chemical structures, that is the models would not fall apart, then we would have our prize.

One fine day in San Sebastian, a glorious city, with the final calculations completed the models did not fall apart. See below.

Our mad pursuit confirmed what Fred Doucet had told me back in 2001. There were two distinct forms of HAS. Two forms that not only differed in their stoichiometries (ratio of Al and Si atoms) but also in their geometry (hexa- and tetra-coordinated Al atoms).

The research, published in 2016, was a personal triumph. When in 1988 in my PhD research I experienced the ‘sweet smell’ of silicon protecting against the acute toxicity of aluminium in fish I had no inkling of the enormity of this discovery. It would be almost another thirty years before we would know why silicon was protective and that we had discovered something that was absolutely fundamental to life on Earth. Perhaps not the structure of DNA but without HAS there would be no DNA. Now there is a thought to take with us into 2025.

Happy New Year

Reading this, I felt like watching an excellent episode of a marvellous film series. You’ve sketched a vivid scenario with a few sentences, and you left the finale to rise above the whole series as if accidentally. Only hinting at the potential for sequels...

I am not a specialist in your field, but I can recognize and appreciate your eloquence with the subject and your readiness to share its beauty with lay people like me. Thank you for letting us all in your lab and giving us a tour. In all your articles or interviews.

Have a great New Year.

Regards, Dan

How lucky the world is to have you as our teacher.